Discover more from Can't Get Much Higher

Your Followers are not Your Fans

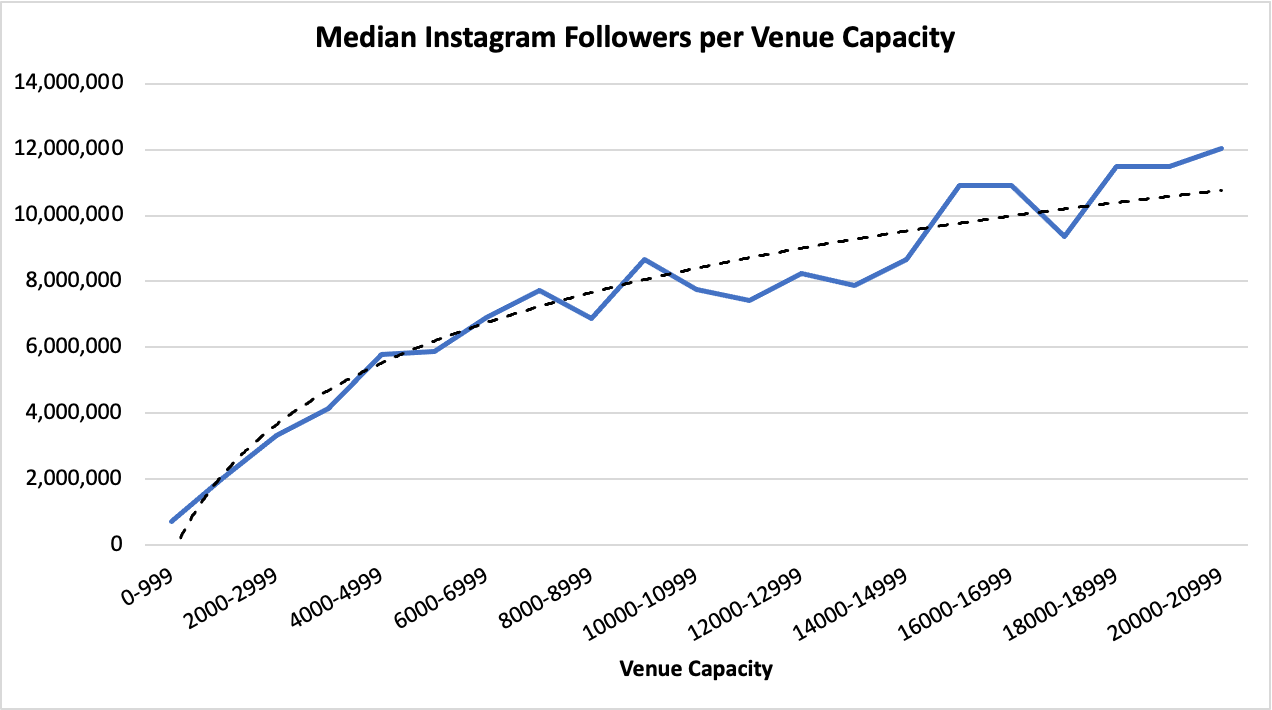

Using data provided by Vivid Seats and Instagram, I learned that social media clout isn't all it's cracked up to be.

In July 2023, rapper Lil Baby canceled 10 dates on his 32-date “It’s Only Us” tour without explanation. Variety soon reported that it was likely due to low ticket sales:

Upon closer examination of the ticket sales charts on Ticketmaster.com, venues for pre-existing dates like Memphis (Sept. 7 at FedExForum) and Seattle (Aug. 12 at Climate Pledge Arena) appear to be less than half-sold …

How is it possible that Lil Baby would struggle to sell out an arena? He has 17 top 40 singles and two number one albums as a lead artist, 22.9 million Instagram followers, and 30.6 million monthly listeners on Spotify. In fact, his biography of Spotify goes so far as to declare, “Some artists define a genre, but Lil Baby defines a generation”. Generational artists usually don’t struggle with ticket sales at venues of any size.

I don’t mean to disparage Lil Baby. He is wildly popular and influential. But in using venue data provided by Vivid Seats and follower data scraped from Instagram, I came to learn that many of these metrics are smoke and mirrors. Your followers - and maybe even your listeners - are not necessarily your fans.

What It Means to Be a Fan

When I first started playing music, I was given some classic advice: “Your friends are not your fans”. I have great friends who share my music and come out to watch me play in many dingy basements, but the point still stands. Your friends like you for who you are, not the three-minute anthems you’re recording in your bedroom.

In the social media age, there’s an important corollary to that rule: Your followers are not (necessarily) your fans. This seems strange. If you’re a musician and somebody is following you on Instagram, for example, that seems like a pretty good signal that they are a fan. But beyond the anecdote of Lil Baby’s cancelled tour dates, I have some evidence to this point.

A few months ago, I got access to a dataset from Vivid Seats, the ticket exchange and resale company, that catalogued over 3600 tours dates for 50 notable artists under the age of 25. Along with some basic information about each tour date, they provided me with the capacity of each venue. I then scraped historical Instagram followers for each artist. This allowed me to see how many followers each artist had when they played a venue of a certain size. Note that I chose young artists because I wanted to make sure that social media would be vital to their careers. For legacy acts from the 1970s and 1980s, like Chicago, a large social media following is usually not a prerequisite for playing a large venue.

In general, there is a relationship between venue capacity and Instagram followers. What this means is that as your social media followers grow, you can expect to play larger venues. That makes sense. You’ve got to have at least some true fans lurking among your Instagram followers.

There are a few things to note about this relationship. First, it’s a positive, non-linear relationship. “Positive” means that as one number increases, the other number will increase too, or as followers increase so will the size of venues that the artist is playing. “Non-linear” means that each follower is not equally as valuable, or going from 1,000,000 to 2,000,000 followers will likely not result in the same increase in venue capacity as going from 10,000,000 to 11,000,000 followers. In this example, the former would likely lead to a larger jump in venue capacity than the latter.

The specifics of this relationship aside, it looks like it goes against my notion that your followers are not (necessarily) your fans. As followers increase, so do the people coming to your shows. That said, I am just plotting the median Instagram following for each venue capacity. There is wild variation in followers for each level of capacity. That variation is where my adage arises.

The Vivid Seats data had 13 artists who played non-consecutive nights at the 9:30 Club in Washington, D.C., a venue that holds approximately 1,200 people. When Dayglow played the 9:30 Club in October 2021, he had almost 243,000 Instagram followers. When Noah Cyrus played the same venue a year later, she had over 6 million Instagram followers. This data suggests that as her number of followers, we’d expect her to be playing venues three to four times the size of the 9:30 Club.

So, what’s the difference between an artist like Dayglow and an artist like Noah Cyrus? Though a smaller population is aware of Dayglow, he has been able to cultivate true fandom among a larger group than Noah Cyrus. This begs the question. What is a true fan? To me, a true fan is someone that is willing to spend money on your music or give your music their undivided attention.

The second part of that definition is important. If fandom required active spend, then people without disposable income (e.g., children) couldn’t be considered fans. Furthermore, in a music streaming economy attention is almost equivalent with money spent given that streaming payouts are currently indirect. By contrast, here are some people that are not true fans.

People who only support you with social media interactions

People who hear your music on playlists but never actively seek it out

People who enjoy just one of your songs

Some of this feels counterintuitive, but it helps explain why Grace VanderWaal and Noah Cyrus were playing the same venue as Dayglow and Cavetown when they respectively had more than 10 times the followers.

Grace VanderWaal won the 11th season of America’s Got Talent. Because of that, she had a great deal of exposure to the television-watching public, a large audience even in the age of video streaming. While many of those people enjoyed her performances, a large swarth probably did nothing to support her beyond watching week-after-week.

Noah Cyrus is in a slightly different situation. She has great name recognition as the daughter of Billy Ray Cyrus and sister of Miley Cyrus. Many people may be following her purely for her family rather than the music that she makes. Dayglow stands in contrast to these two. Not only has he continued to play venues larger than his Instagram following suggests he should be playing, but there’s a high chance if you’re following him on Instagram that you are a true fan.

The musical world is increasingly measurable. Pull up any artist’s Spotify page and you can see exactly how many times their songs have been played. Pull up their TikTok page and you can see exactly how many times their last post was liked. But many of these numbers obscure the point that the power of music is not in generating as many digital interactions as possible but in uniting listeners via song. The artists that can do that are the ones to watch, no matter what metrics you see attached to them on the internet.

A New One

"frog - Recorded at Metropolis Studios, London" by Cavetown

2023 - Acoustic Bedroom Pop

Cavetown is one of those artists who continually plays larger venues than their social media following suggests they should be playing. On the live rendition of their song “frog” - recently recorded for the streaming service Deezer - you can understand why.

The refrain initially comes off as strange: “I'm your frog / Kiss me better all night long”. I can’t think of any other song where lovers are compared to frogs. But it’s in creating novel imagery that Cavetown inspires you to want to go deeper into their catalogue.

An Old One

"Seasons in the Sun" by Rod McKuen

1964 - Somber Singer-Songwriter

The first paragraph in Rod McKuen’s 2015 Richmond Times-Dispatch obituary sums up his career succinctly:

Rod McKuen, the husky-voiced "King of Kitsch" whose avalanche of music, verse and spoken-word recordings in the 1960s and '70s overwhelmed critical mockery and made him an Oscar-nominated songwriter and one of the best-selling poets in history, has died. He was 81.

Though no critic would be caught in this circle, Rod McKuen had many true fans during his lifetime. That same obituary claims, “Worldwide sales for his music top 100 million units while his book sales exceed 60 million copies”. Despite that, you will not only struggle to find true fans of McKuen today, but you will struggle to find anybody who knows his name. I think that’s a shame.

Though his work can be overwhelmingly saccharine, some of it is quite compelling, compelling enough that Frank Sinatra did an entire album of his songs. “Seasons in the Sun” - which later topped the Billboard Hot 100 in 1974 by Terry Jacks - is a slow dirge where McKuen’s voice barely comes above a whisper. But if you listen closely, it’s hard not to be drawn in by that whisper.

Want to be one of my true fans? Add my latest song to a playlist and share it with your friends.

Subscribe to Can't Get Much Higher

The intersection of music and data

Thanks for sharing the Rod McKuen version of "Seasons in the Sun." I hadn't heard it before, but it's an interesting bridge between the original "Le Moribund" by Jacques Brel and the Terry Jacks version.

QED, Chris! Thanks for doing the math on this evergreen topic. Bill Bernbach, the closest to a sage in the ad business put it best long before the dawn of social media: ‘a principle isn’t a principle unless it costs you money...’