If you read this newsletter each week, you’ll know that I typically rant about some topic, usually one that brings together music and data. Then I recommend both a new song (i.e., one released in the last few weeks) and an old song (i.e., one released at least five years ago).

You’ll still get a rant from me this week. (It’s about crappy duets.) But the song recommendations will come from my friends at Songletter, a publication that delivers one to two songs to your inbox each week. Some of those recommendations will be new. Others will be old. But in either case, they will open your musical mind. Subscribe to Songletter if you’re looking for some exciting music.

You’re Due-ing-et Wrong!

Sometimes life leaves you disappointed in ways that you didn’t think it would. Here’s an example. The Gaslight Anthem, Bleachers, The Killers, and Zach Bryan are four of my favorite artists from the last 20 years. Furthermore, Bruce Springsteen is my favorite artist of all-time. The good news? In the last three years, all four of those aforementioned artists have released a duet with Springsteen. The bad news? Each of those duets was sort of underwhelming.

I think part of the issue with these duets is Springsteen himself. And the issue is the same reason I love much of his music. He is such a singular musical figure that his presence on another’s track can almost feel distracting. It’s kind of like asking Barrack Obama to make a five-second cameo in a movie. His presence would take your mind out of the film for a few moments while you think to yourself, “Hey, that’s the former president.” To me, Bruce Springsteen is the president of music.

I think this issue goes beyond The Boss, though. Over the last few years, there have been a ton of high-profile duets that have left me wanting more. Taylor Swift and Post Malone’s “Fortnight”. Post Malone and Morgan Wallen’s “I Had Some Help”. Ed Sheeran and Beyoncé’s “Perfect”. I could go on. But my point is that these are often pairs of artists who have released music that I enjoy who come together to release a dud.

Of course, the disappointing duet is nothing new. Paul McCartney and Stevie Wonder — arguably the 20th century’s greatest artists — managed to create the abysmal “Ebony and Ivory” in 1982 with the help of legendary producer George Martin. But I think there are some specific forces that are driving this current trend.

The Influence of Streaming on the Duet

Merriam-Webster defines a “supergroup” as “a musical group made up of established, prominent musicians.” If that sounds too generic, they provide three examples.

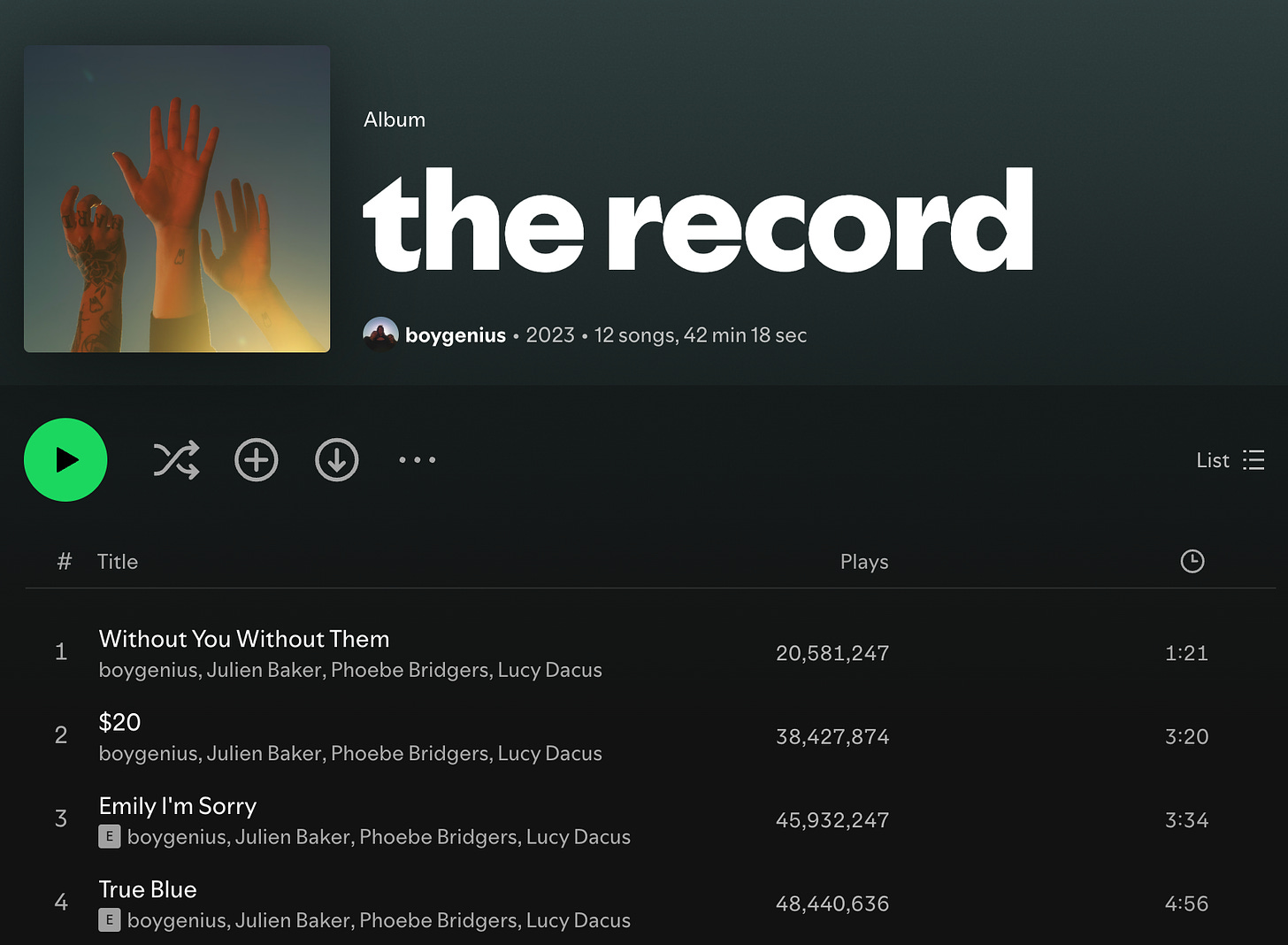

boygenius: Collaboration between celebrated songwriters Phoebe Bridgers, Julien Baker, and Lucy Dacus

The Traveling Wilburys: Collaboration between rock legends George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Tom Petty, Roy Orbison, and Jeff Lynn

Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young: Collaboration between folk rock pioneers David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Graham Nash, and Neil Young

If you listen to any of these three supergroups on your streaming service of choice, you’ll notice something subtly different between how boygenius is presented compared to their male progenitors. Whereas a Traveling Wilburys’ record will simply list the group name as the artist on each track, a boygenius record will not only list the group but also each member. Why would these albums be credited differently?

Because streaming services make it easy to see every release from an artist — namely by clicking that artist’s name — there is a strong incentive for artists to make sure they are directly credited on a track list. Now, if someone is enjoying a boygenius song, they can quickly get to the music of Phoebe Bridgers, Julien Baker, and Lucy Dacus. Furthermore, if you are a fan of one of those three, the release of the boygenius record will likely be surfaced to you because each member is listed. In other words, streaming not only incentivizes collaborations but it incentivizes listing collaborators in this way.

The problem is that because there is significant upside to releasing collaborations, they can often be lazy, especially on expanded editions of albums. Here’s why. You want some more streams with minimal effort? Just mute your vocal in the second verse of a song you’ve already released. Email that version to a potential collaborator. Have them re-sing the verse. Put it out. You’ve got a “new” song without even having to leave your couch.

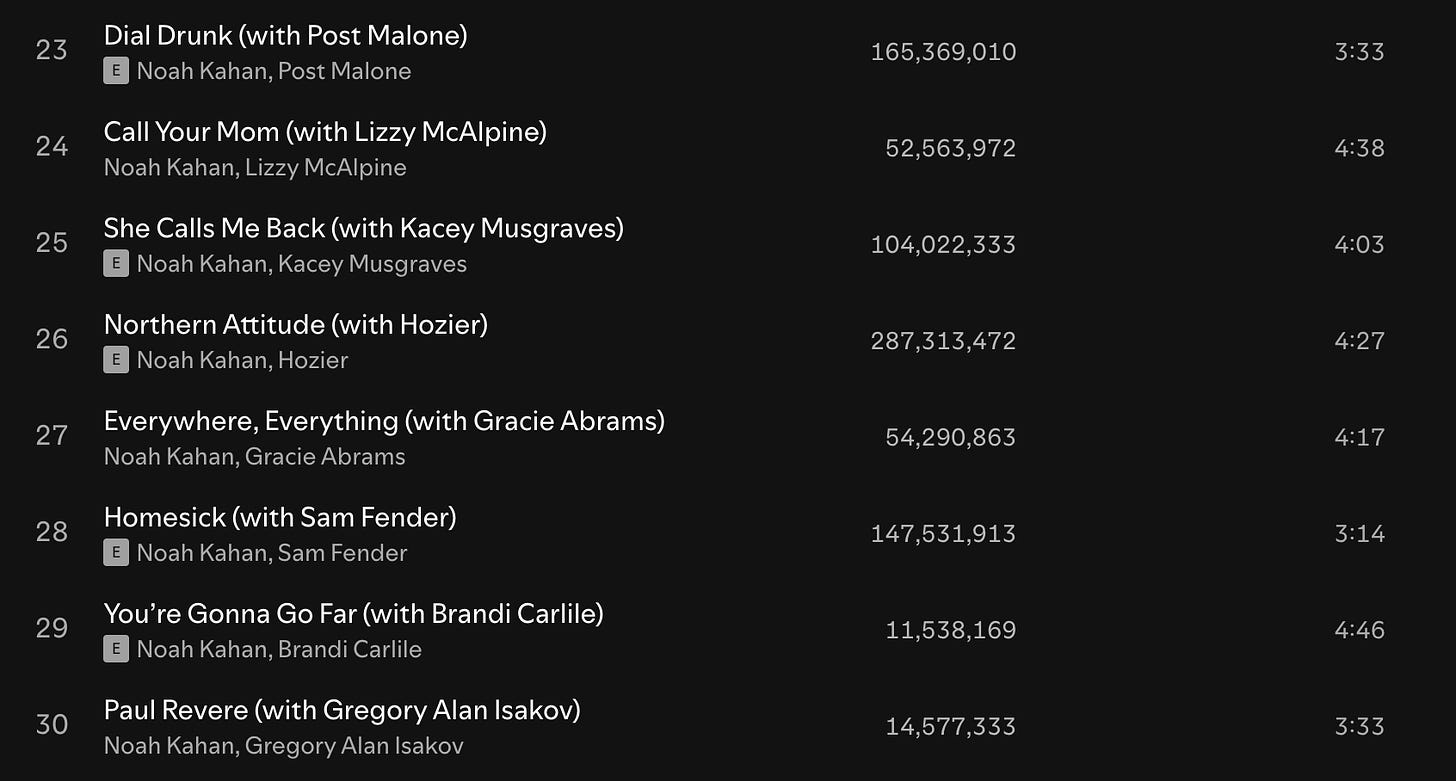

If you want to see this strategy in action, check out songwriter Noah Kahan’s output over the last few years. In 2022, Kahan released the 14-track album Stick Season. The next year he added seven tracks to the album while also releasing remixes of many of those songs as duets. In 2024, he assembled all of the songs into a 30-track, mega-version of the album, now titled Stick Season (Forever).

Of course, duets have been used to legitimize an artist and expand their fanbases for decades. Whitney Houston’s debut album, for example, featured collaborations with Jermaine Jackson and Teddy Pendergrass. But streaming has made this incentive stronger, much to the detriment of the duet.

The Influence of Hip-Hop on the Duet

During the second half of the 20th century, rock music became so ubiquitous that it came to influence nearly every popular genre. In the last three decades, hip-hop has overtaken rock music as that cultural force. Because of that, we’ve seen other styles co-opt many elements of the Bronx-born genre. You can hear that when trap hats pitter in the background of country songs. You can hear it when pop vocals bear more resemblance to a rapper’s flow than a Tin Pan Alley-style melody. But you can also hear it in the disappointing duets that have circulated in the last few years.

One of the most classic song forms in hip-hop is the posse cut, or a song where each verse features a different rapper. This song form goes back to the origins of the genre and continues to be influential to this day with artists like Kanye West, Migos, and Jack Harlow continuing to use it.

Part of the reason the posse cut is so effective is because hip-hop songs have a ton of flexibility in how an artist can perform a verse. On the posse cut “Forever” featuring Drake, Lil Wayne, Eminem, and Kanye West, each rapper brings distinct flavor to their verse even though the instrumental behind the verse is the same. This is also why we see remixes of pop songs with rappers work well. You can give Cardi B or Kendrick Lamar a verse on a song in most genres and they will be able to create intrigue that is distinct from that of the vocalist.

The posse cut sadly doesn’t translate well to other genres. You can’t take another vocalist and let them re-sing a verse on your song and assume that it will improve or even be interesting. The melody and lyrics of that verse are still the same. Unless your collaborator is given the flexibility to rewrite and reimagine their verse, it will likely feel like they mailed it in. That’s the feeling I get from many prominent duets of the last few years.

So, if I think duets have been dumbed down by the incentives of streaming and the misconception that singers and rappers have the same impact by featuring on a song, then what makes a good duet? As I dug through some of my favorite duets, I realized that the answer was found in the title of fantastic collaboration between Marvin Gaye and Kim Weston: it takes two.

A great duet has to be a true collaboration between talented artists. It has to let each half shine. It has to see two distinct styles mix in unexpected ways. This is hard to accomplish if your duet partner is just coming in to sing one verse and maybe some harmony on a chorus. It is hard to accomplish if you never see your duet partner in person. It is hard to accomplish if you don’t trust your duet partner to take creative liberties.

There are still great duets around these days. Though I complained about Zach Bryan’s duet with Springsteen at the beginning of this piece, I think “Dawns”, his 2023 collaboration with Maggie Rogers, is one for the ages. But I think there are strong forces telling us to take the easy way out when it comes to collaborating. Don’t take the easy way out. Collaborating is hard. But it’s also worthwhile.

A New One from Songletter

"Hiding" by Lykke Li & Ben Böhmer

2024 - Indietronica

Released just days ago, this track marks Lykke Li's first new collaboration in five years. We absolutely loved how she came together with the young, talented Ben Böhmer to make this song.

An Old One from Songletter

"Way Down Deep" by Jennifer Warnes

1992 - Singer-Songwriter

Seven years ago, I visited a high-end audio store to test one of their top sound systems. They led me to a special room in the basement and played this as a test track. It has stayed with me ever since. I can't decide if it was the incredible bass or Jennifer Warnes' beautiful voice that hooked me, but those speakers were a stunning introduction to her music

As I mentioned at the beginning of this newsletter, this week’s song recommendations came from Songletter, one of my favorite publications around. If you want great recommendations sent to your inbox twice a week, sign-up for Songletter below.

Also, shout out to the paid subscribers who allow Can’t Get Much Higher to exist. Subscribers get four additional newsletters each month and access to our archive. Consider becoming a paid subscriber today!

Recent Paid Subscriber Interviews: Royalty-Free Music • Microphone Engineer • Spotify’s Former Data Guru • Running an Independent Venue • John Legend Collaborator • Broadway Star • What It’s Like to Go Viral • Adele Collaborator

Recent Newsletters: What Happened to Instrumentals? • I Miss You, Buddy Holly • Blockbuster Nostalgia • Pop Songs & Baby Names • Recorded Music is a Hoax • On Dying Young • Selling Out

Want to hear some of my favorite duets? Check out the playlist below.

Have never understood why people despise "Ebony & Ivory," which here is described as "abysmal."

Is it just the overall sweetness that to many is mere kitsch and saccharine?

Is it like getting (what do the kids call it) "rickrolled" or something?—once everybody decided to hate it, the ridicule took on a life of it's own?

Would sincerely love to hear what the song's artistic demerits are. Been wondering this for years and years.

I like the post and it makes me think that it's remarkable that "Four Five Seconds" (Rihanna, Kanye, Paul McCartney) worked as well as it did.