The Medium is the Message: Changes in Popular Music Since the 1950s

Stat Significant takes over Can't Get Much Higher to show us how radically popular music has changed over the last few decades.

The community of people using data to write about pop culture is very small. That’s why I was excited when I came across Stat Significant a few weeks ago. Stat Significant is a weekly newsletter featuring data-centric essays about movies, music, sports, and more. They’ve delved into some fun questions over the last year.

This week, I am featuring one of their pieces here on Can’t Get Much Higher. If you like what you read, check out their newsletter. Also, if you want to contribute to Can’t Get Much Higher, feel free to reach out.

How Has Music Changed Since the 1950s?

For 400 years, music publishing was dominated by sheet music. The earliest known sheet music was a set of liturgical chants published in 1465 shortly after the Gutenberg Bible. Before the printing press, a composer's works had limited geographical reach, with music access limited to moneyed aristocrats. However, through mechanized music printing, an artist's work could be archived and distributed at relatively low cost to consumers worldwide. The printing press would be the first technology to disrupt the music industry.

Flash forward to 2014. Spotify and iTunes exist, while sheet music is used exclusively by band geeks and symphony orchestras. The Michigan-based funk band Vulfpeck releases Sleepify, a ten-track album devoid of audible sound. Each track runs 30 seconds long and consists solely of silence. Sleepify is distributed via Spotify, where the band encourages fans to play the album on a loop while they, well, sleep.

The songs on Sleepify received 5.5 million plays, making Vulfpeck a tidy profit of $19,655.56. Somehow three hundred seconds of silence became a rousing commercial success.

Since the time of printed compositions, popular music has churned through a variety of mediums: live performance, radio, vinyl, cassette tapes, music videos, CDs, Napster, Limewire, iTunes, Pandora, Spotify, YouTube, Apple Music, and TikTok. With each change in distribution, artists have adapted. So, how has popular music changed throughout the years? And how has listening format impacted the content produced by musicians?

Dataset and Methodology: How Has Popular Music Changed?

Our goal is to track changes in song composition for popular music. We'll define popular songs as works listed on the Billboard Hot 100 and utilize Spotify's database of song attributes to track musical changes. This database includes information on danceability, duration, instrumentalness, speechiness, and positivity song features.

Is Popular Music Changing in Length?

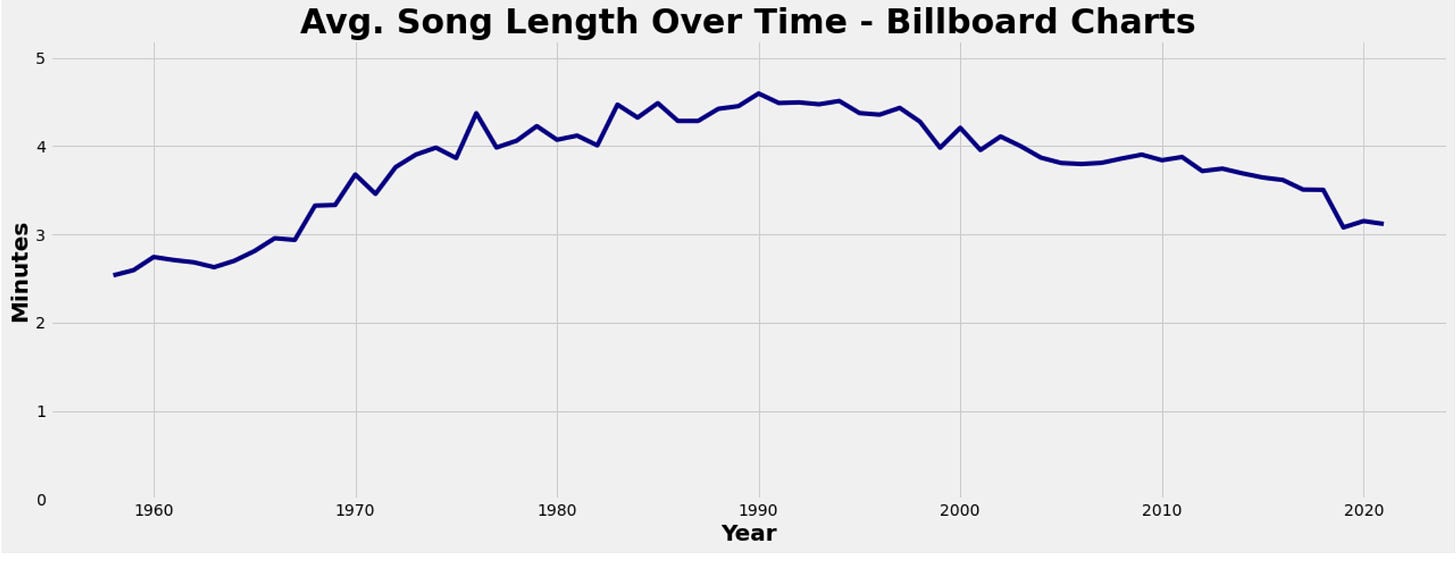

In the late 1950s, the 45-rpm record format overtook the 78-rpm design, expanding average music capacity from 4–5 minutes per vinyl side to 9–12 minutes. This increase would be the first of many innovations in data engineering. The second half of the twentieth century saw rapid advancement in form factor and storage capacity as album design progressed from vinyl to cloud storage. As time constraints disappeared, average track lengths increased, with popular song duration peaking in the mid-90s.

When duration peaked, records and cassettes were the predominant format for distribution, and music videos encouraged in-depth storytelling alongside hit songs. Everybody wanted their MTV and didn't seem to care how long music lasted if played alongside pleasing visuals.

Starting in the late-1990s, song length began to dip. This fall stems from two paradigmatic shifts in music economics. First, the introduction of iTunes and streaming led to a decoupling of songs and albums. Artists began focusing on the commercial maximization of individual tracks over cohesive album concepts. Second, streaming services typically pay per play, rewarding artists for the number of listens as opposed to total listening time. Streaming ten 31-second tracks pays more than a single stream of a 310-second song.

Is Music A Winner-Take-All Market?

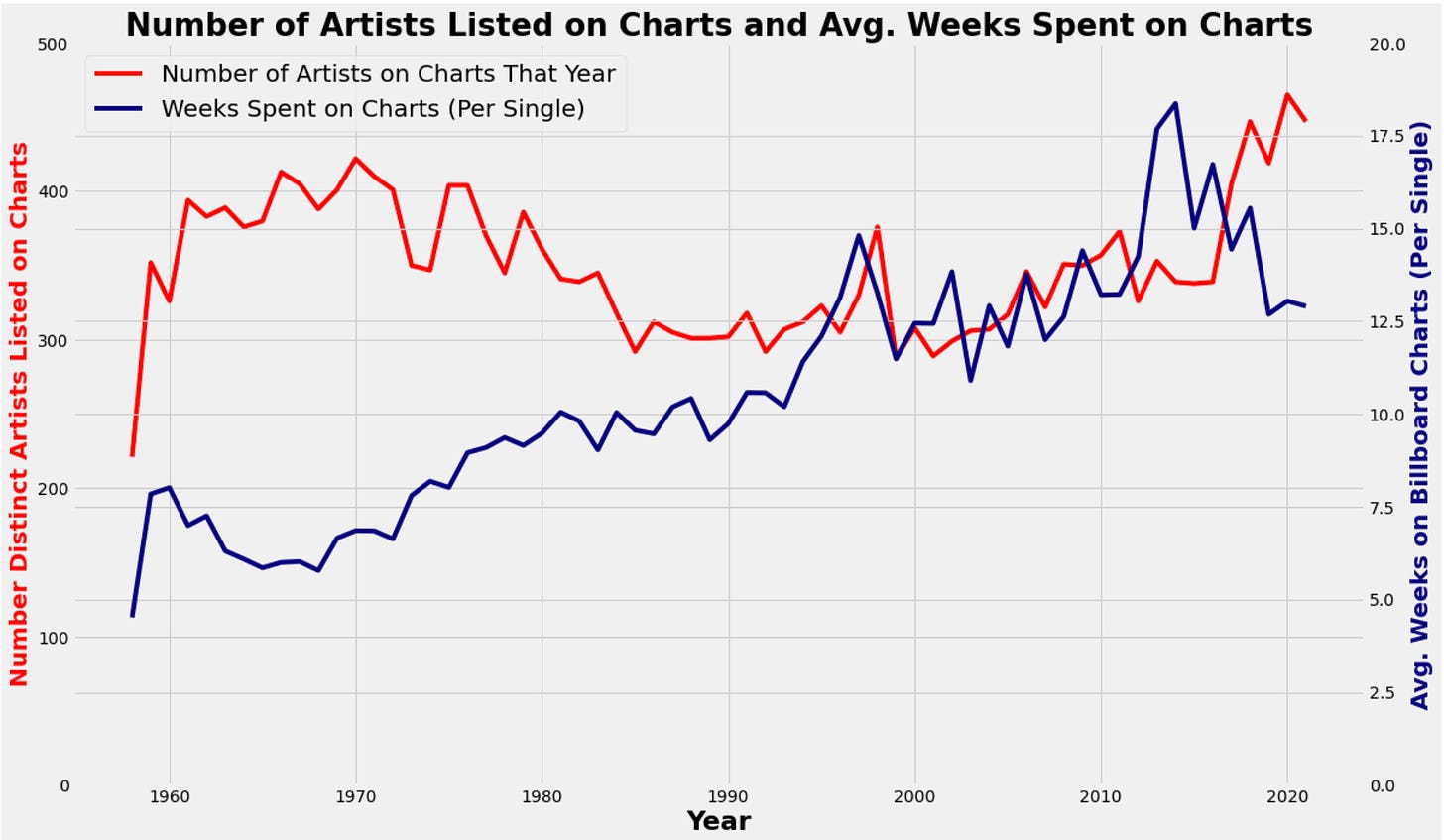

As a marketplace, the music business connects listeners with free time to artists who wish to occupy that free time. Until recently, record labels were an overwhelming determinant of artist reach, as a cartel of brands functioned as gatekeepers for physical music distribution (e.g., CDs and vinyls). Then Spotify came along.

Spotify and musicians exist in an unhappy marriage marked by asymmetric power dynamics. Spotify emphasizes its role as a democratizing force within the music industry, providing consumers with ease and artists with decreased barriers to entry. I always assumed this last point was a means of obfuscating streaming's negative impact on artist compensation. But it appears the democratization argument holds some weight:

Since Billboard's inception, artists and labels have continuously maximized average chart tenure for hit songs. From the 1950s to the mid-2010s, a successful single remained on the charts for longer periods, while the number of artists listed on the charts remained mostly flat. In the middle of the 2010s, when streaming began its ascent, we see a trend break in chart longevity and quantity of artists listed. More artists make the charts for shorter periods.

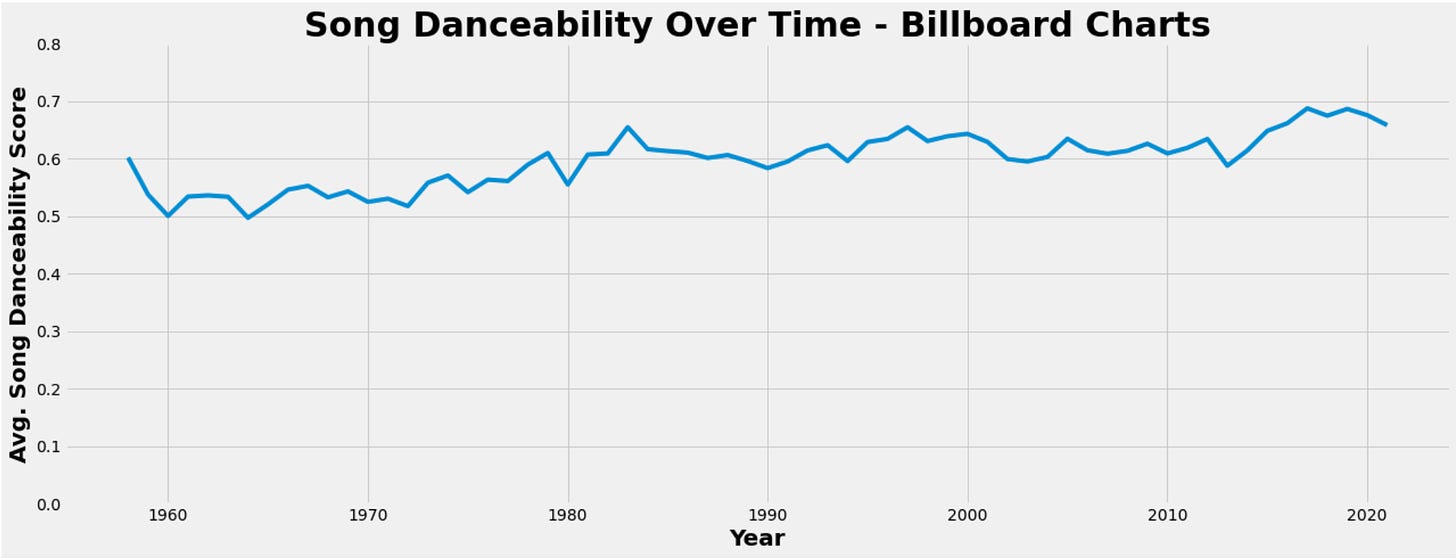

Is Music More or Less Dance-y?

What makes a song danceable? People have cut loose for ages, regardless of Spotify's danciness ranking. It's not like people in the late 1950s abstained from dance because they were holding out for Outkast or Lil Baby. No, they listened to Bobby Darin and Elvis and thought, "Wow, I love dancing to this sufficiently dance-able music." Yet according to Spotify, popular music has increased in danciness over time:

So, what is driving this purported uptick?

Recency Bias in Spotify's Algorithm: Popular dance music typically exists within distinct cultural epochs (e.g., 50s: Doo-Wop, 60s: Motown, 70s: Disco, etc.). Would you expect the same playlist at a wedding and a nightclub? No. Wedding band serve a broad age range, often catering to older demographics by playing from a list of well-worn classics, while nightclubs focus on music for young people. Spotify's algorithm may assess song attributes based on its base's dance preferences.

The Importance of Live Music: The digitization of music distribution offers consumers abundant music content in return for an affordable subscription fee. In response, music acts shifted their profit centers from record sales to live performances. And what do people like to do at music shows? Dance.

Industrialization of Music Production: In 1998, Cher's mega-hit single "Believe" made prominent use of auto-tune. The computerized effect was a central feature of the song and served as a watershed moment for the mechanization of music production. Since that time, song creation has grown increasingly computerized, with major studios adapting digital workflows. This process may produce optimally dance-able beats.

Where Did the Instrumentals Go?

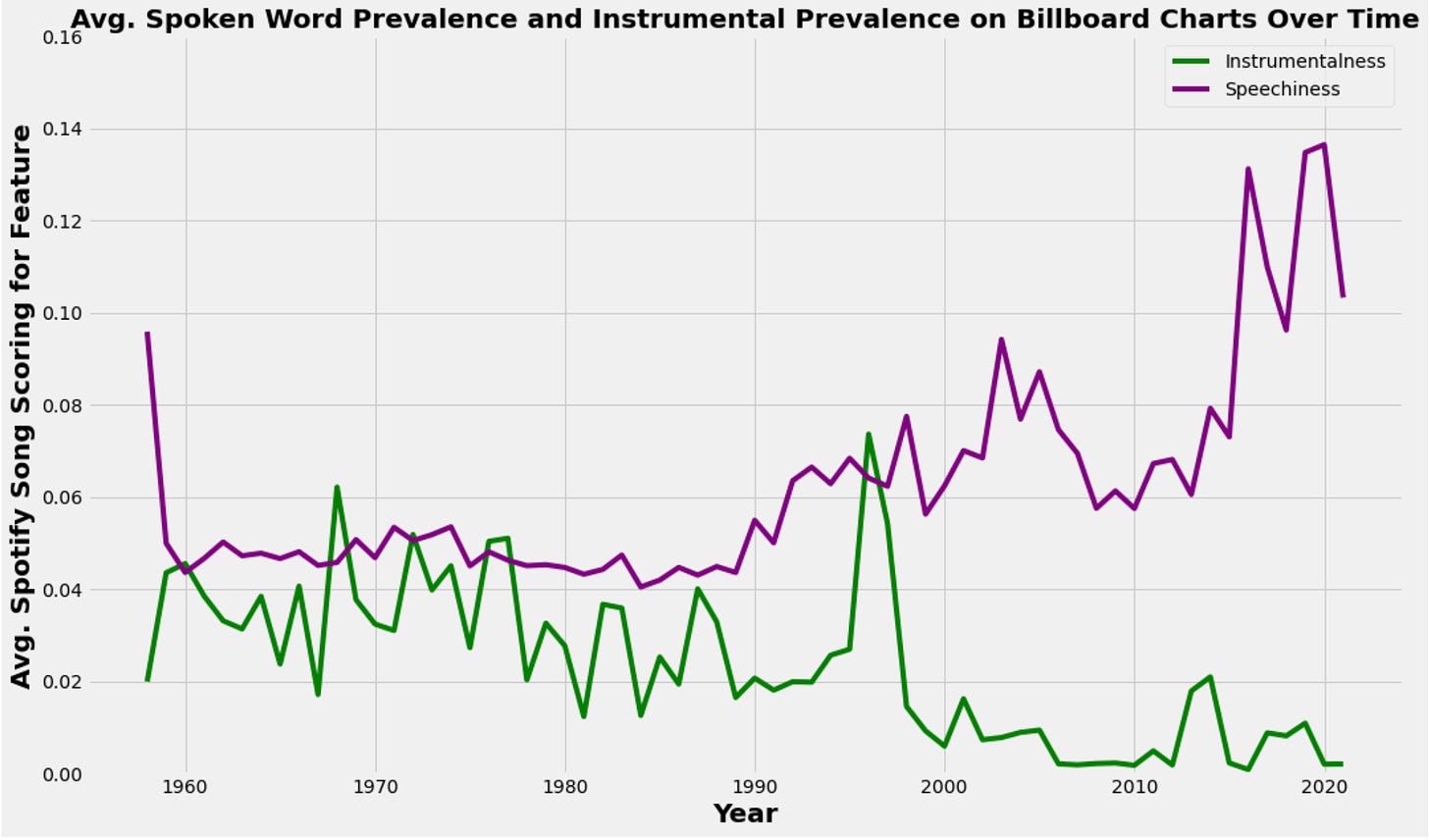

There is a time-honored tradition in rock DJ-ing known as the "toilet track," an established staple of songs long enough to allow the DJ a trip to the bathroom. Lynyrd Skynyrd’s "Freebird". Queen's "Bohemian Rhapsody". Led Zeppelin's "Stairway to Heaven". These are prototypical examples of high-quality toilet tracks with extended guitar solos. But the toilet track may be a thing of the past, as Spotify's dataset observes a decrease in the prevalence of unaccompanied instrumentals, concurrent with an increase in lyric-driven music.

The fall of instrumental music underscores rock's declining influence, and the rise of speechiness emphasizes rap's growing cultural dominance.

Final Thoughts: The Ever-Changing Medium and Ever-Responding Message

Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan is well-known for prophesizing a fragmented media landscape defined by ever-changing advances in distribution. His theories read as inevitable when evaluated against our current world of content abundance. McLuhan, however, was writing in the 1960s, when people bought Elvis records, watched four TV channels, and knew nothing of Elon Musk.

In his book Understanding Media, McLuhan highlights the transformative power of technological progress, which he broadly terms "media" or "medium":

The medium is the message. This is merely to say that the personal and social consequences of any medium - that is, of any extension of ourselves - result from the new scale that is introduced into our affairs by each extension of ourselves, or by any new technology.

According to McLuhan, technological progress "shapes and controls" human interaction, not any one piece of content distributed via these new-fangled platforms. So, for example, it's the advent of social media that spurs change in human relations, not any one tweet that follows.

Streaming offers a world of democratized music distribution and consumer abundance. Musicians can easily disseminate works in a market characterized by increased artistic control, and for $9.99 a month, users get access to every song in human history. Today’s music industry - from songwriting to album promotion - is thus organized in service of a recurring $10 price commitment.

And with that, let's return to Sleepify. While overwhelmingly bare in content, Sleepify’s success both epitomizes and mocks contemporary music's maniacal quest to maximize consumption. In this extreme case, a silent album generated nearly $20k in earnings but would have sold zero copies of sheet music in the late 1400s.

Vulfpeck's muted masterpiece is uncomplicated yet far-reaching in its message, as the album required minimal production, simultaneously critiqued and exploited Spotify's business model, and made decent money in the process. It's also an example of artists acknowledging the regrettable business dynamics of streaming while simultaneously adjusting to the new norm.

Streaming is here to stay — until the next disruption in music distribution — the artists that adapt their message will conquer the new medium.

Want more from Stat Significant? Subscribe to their newsletter for a weekly dose of culture and analytics.

I can’t believe there’s no reference to John Cage’s “4’33”” which is a seminal work of musical deconstruction to the point it can’t really be considered music. Performance Art, sure, but not music. Indeed, it is rather commentary on music, specifically the performance environment. Seems like Vulfpeck is making the same statement.

"Musicians can easily disseminate works in a market characterized by increased artistic control..." You mean upload all over the world, not get paid for it, and not know who's listening or how to reach them, while competing with actual silence (and losing in that competition)?