Spotify's Former Data Guru Tells All: A Conversation with Glenn McDonald

Glenn McDonald spent the last decade shaping how Spotify curates and recommends music. In his new book, he explains how it all worked.

After reading Glenn McDonald’s forthcoming book You Have Not Yet Heard Your Favourite Song, I thought about ending this newsletter. Very broadly, this newsletter seeks to explore the modern music industry and various musical puzzles via a data-first approach. McDonald’s book does all of that better than anyone else.

Have you ever wanted to know how Spotify recommends music? How they pay artists? If streaming will grow or shrink the music industry? If streaming has destroyed the album? It’s all in McDonald’s book. I read so many books about music and the music industry, and I can’t recommend this one enough.

A Conversation with Glenn McDonald

I want to start with a quote from your book: “There's plenty of music. There's more music than you have time, but if you have an hour to listen, joy awaits. There are no wrong directions. Listen until you feel yourself drawn, and then follow your ears.” When was the first time you remember having a powerful musical experience?

I remember at some point in my childhood, I got a record player. I didn't have very many records, and I didn't have very much money, so I was mostly listening to records that my parents had. My parents met being folk singers, so there was a lot of Simon & Garfunkel, Gordon Lightfoot, and John Denver. But for other genres, I really only had the car radio. That’s how I developed my own tastes.

One day, I remember hearing “Hold the Line” by Toto on the radio in Dallas. It has a distorted guitar and I was like, “Whoa, what is that noise? That's the heaviest thing I've ever heard.” Looking back, that’s hilarious because it’s Toto, but that’s the sound that led me to Boston and Rush and Blue Öyster Cult and Black Sabbath. Now, I’m into black metal and ridiculously overblown power metal. It’s all attached to that one chord from Toto.

Did you ever get the bug to start making music like your parents?

Yup. I have stuff out there. It’s not very good. I played cello as a kid. Then I learned the guitar. I can play the drums a little. I think you become a better listener when you have some experience making music.

So, you are a big music fan, but you’ve spent much of your career working in software. I was looking over your LinkedIn profile and your employment history is very interesting. You worked at Lotus and AT&T and Google and a few other places, usually with some title that involves the word “Designer”. You then get to Spotify and are given the title “Data Alchemist”. Can you explain what that term meant and how it came about?

I worked at the Echo Nest in the 2010s. Before we got acquired by Spotify, we were just a little company trying to get attention. I was very good at building things that the press would cover. If I got interviewed about those things, they’d always ask my title, and I’d say “Principal Engineer”. I mean that’s just a level of software developer, but people that were interviewing me didn’t understand that. So, these articles would come out, and they would make it sound like I was the only developer at the company. I was always embarrassed by that because the two founders were software engineers and they were definitely more “principal” than me.

To stop that from happening, I started telling people that I was a “Data Alchemist”. I like that because it sort of sounded like “Data Scientist”, but the alchemy part suggested that I was trying to make something, which I was. That seemed like a better metaphor for what I was doing. Jim Lucchese, who was the CEO of the Echo Nest, loved making people live with their own jokes. As soon as he saw the article where I called myself a “data alchemist”, he was like, “That's it. That's your title.”

And that came with you when Spotify bought the Echo Nest?

Yes. There actually was a formal title in the Spotify HR system called “Data Alchemist”. It had a job description and everything. There was never another one of me. In theory, there could have been, though.

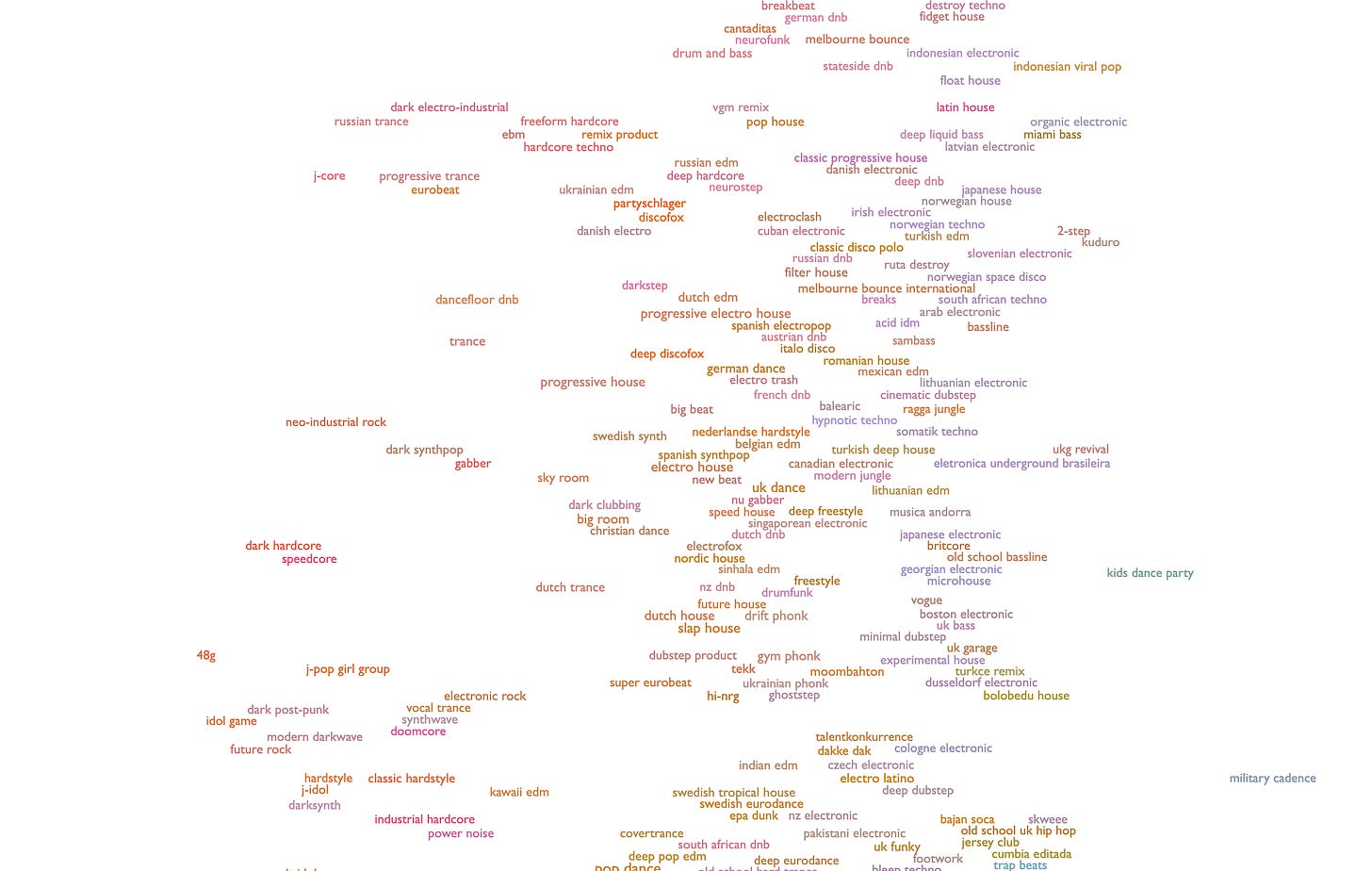

In your role as Data Alchemist, you created Every Noise at Once, which sought to categorize the world’s music. Part of the project was that categorizing music and genre is valuable from a business perspective for Spotify. But your quest for organization seems to run deeper. What do you think is the importance of that work you did?

At the beginning, that project was tactical. We needed a genre radio solution at the Echo Nest because people kept asking us for it. That was how the genre system started. There was no philosophical grounding.

As we worked on it over the years, I realized what we were really doing was finding communities around the world. These were music communities, listening communities, artists communities, fan communities, and so on. That insight justified my persistence with it because if you can find communities and show them to themselves, you can help them thrive. So, there were plenty of uses for that at Spotify, but the level of obsessive detail that we put into it was not something they necessarily cared about.

In your eyes, is the act of naming something important? Like it gives a community legitimacy?

The genre map would work with no names. It could just be symbols or numbers. You could go to genre 1235 and be like, “Wow, that’s my sound!” Giving them human-readable names makes the map more navigable, though. And I should say that we didn’t create all of those names. Most already existed.

Last year, Spotify told my girlfriend that her favorite genre was “Alt Z”. She was confused at first and then looked at it and was like, “Oh, yeah, this is all my favorite stuff.” I don’t know if you had a hand in defining that genre specifically but tell me how you would go about deciding when a cluster of music was a new genre. Then tell me how you’d name that genre.

That’s one I actually did name.

I guess I picked well [laughs].

I had all these tools at Spotify that would find unlabeled clusters that we had some data evidence to say belonged together. Typically, that cluster of songs or artists shared common listeners. You’d have to actually play the music to decide if it was really something you’d refer to as a genre. Sometimes a cluster would appear that was really just a bunch of artists on a single soundtrack. That’s not a genre. But sometimes you’d listen and be like, “I know these artists. They make sense together.” Naturally, the next thing you’d ask is, “Does this have a name?”

For “Alt Z”, it was artists that fell into the “Indie Pop” category. But “Indie Pop” is way too broad, so I had to make something up. I could have called the genre “Generation Z” because most of the listeners were young. That felt boring, though. What struck me is that the music felt alternative and Gen Z-ish. I also liked the idea that the keyboard shortcut for undo was Control + Z.

When you listen to the artists that fall under that category, the name makes sense.

It’s one of the rare fanciful names that works. It got a lot of attention because some big artists fell into that category. It was always nice when you would tell someone they like a genre with a weird name like “Alt Z” and they’d be like, “What’s that?” Then you’d show them, and they’d be like, “Oh! That’s my taste.”

Were these clusters always based on listeners?

I talk about this more in the book, but it’s not just listening pattens. Something like “Vegan Straight Edge” was based more on lyrical content and musical style. Some other styles were geographic. Some were historical.

Do you think this system fell short in any regards?

Ultimately, categorizing the world’s genre communities shouldn’t fall on the shoulders of a corporation. The fact that I got laid off is proof of that. Companies disappear. People lose jobs. These communities exist in the real world. They are self-organized and just show up in our information space.

We’ve been touching on many ideas from the book, but let’s talk about some specifics. In the book, you present a thought experiment comparing the CD era to the streaming era. Back in the day, there were people who would buy 100 CDs a year. Assuming a CD costs $15, that’s $1500 in spending. At the same time, there were people who might buy one CD per year. Both now pay the same amount for a yearly streaming subscription. Do you think streaming will grow industry revenues to new heights because you will get more casual listeners spending more than they would have 20 years ago? Or do you think they will never close the gap from the less spending of power listeners?

According to the RIAA, we’ve already surpassed the peak of the CD era in terms of industry revenues. Adjusted for inflation, we’re only like 60% or 70% of the way there. However, I think the peak of the CD era was a bit exaggerated because people had to pay for music that they already owned on cassette and vinyl.

It seems very reasonable to me to imagine that the streaming peak will be higher. One core tenet behind the music industry is that you make people aware of music and then you sell them other things around that music, like concert tickets and merchandise. Streaming makes getting music to people easier than ever before.

There’s this idea that the internet flattens culture. You make the case in your book that the opposite is likely true because local scale was hard to achieve in the physical era. Do you think places can still maintain their local identity as we have access to all the music at once?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Can't Get Much Higher to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.