Mic Check, One, Two: A Conversation with Joey Krieger

At only 28, Joey Krieger is the head of R&D at a respected microphone manufacturer. We sat down to talk about what makes a great mic and why vintage mics remain popular.

When I spend time talking about the magic of a record, I am usually talking about how that record moves me emotionally. But I think the magic of a record runs deeper than the meaning of the song you are listening to. I think part of the magic is that music can be recorded at all, that we can capture something so ephemeral and play it over-and-over again.

Joey Krieger knows more about this magic than most people. At only 28, he’s the head of R&D at AEA, a vaunted manufacturer of ribbon microphones and preamps in California. Two weeks ago, Krieger and I sat down to talk about how recording works, his journey to such an esteemed position at such a young age, what makes ribbon mics superior to other mics, and why people are still repairing 80-year-old microphones even though microphone technology has improved.

A Conversation with Joey Kreiger

Every time I use a microphone, it feels like magic. I am capturing something, namely sound, that feels very ethereal. As someone that works with microphones in a very technical way, do you feel that magic?

I think the magic is just a little bit further away. It is all just physics. And it’s sort of magical that all of that physics works. But it’s even more magical that people were able to figure out all of this stuff with electricity and magnetism and semiconductors to make it work.

Can you give me a very simple overview of how a microphone actually captures sound?

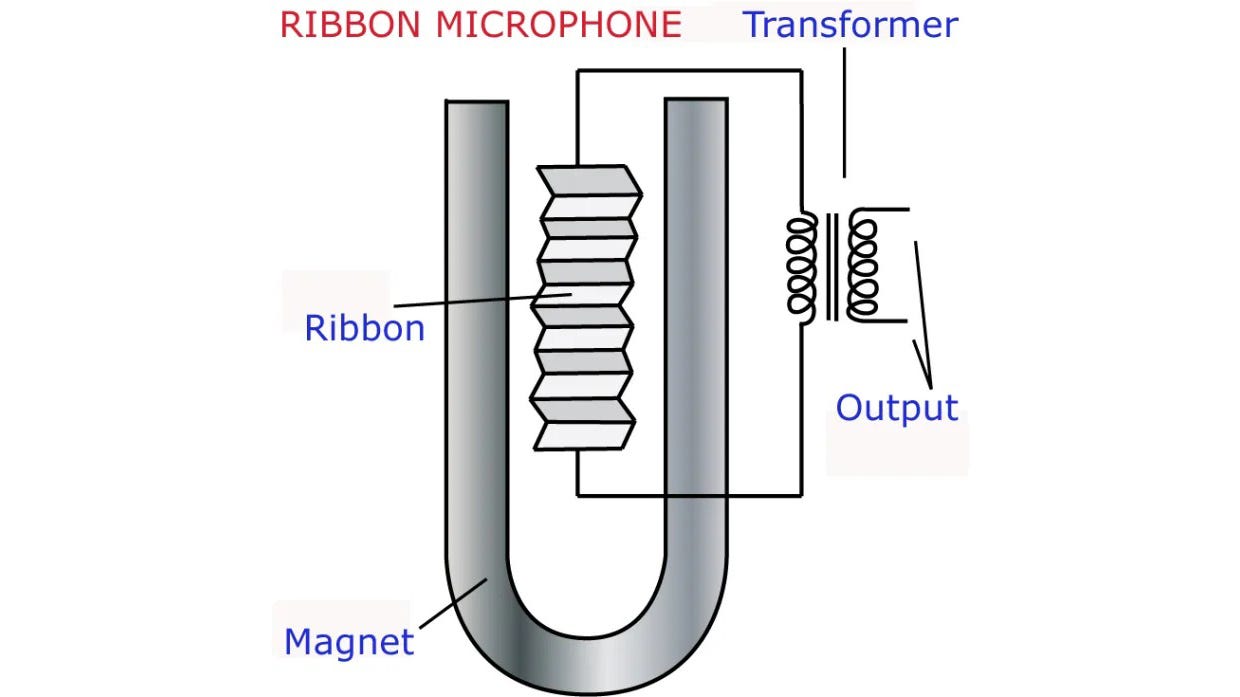

Sound is propagating waves in the air. The goal of a microphone designer is to create something that accurately captures those vibrations across the whole frequency spectrum. There are a variety of ways to do that. With ribbon mics and dynamic mics, it’s done by vibrating some sort of metal in a magnetic field. That vibration creates a small AC voltage that then goes through a transformer and can be amplified through a preamp and then eventually converted into ones and zeros or sent out through a PA system where it's converted back into acoustic sound.

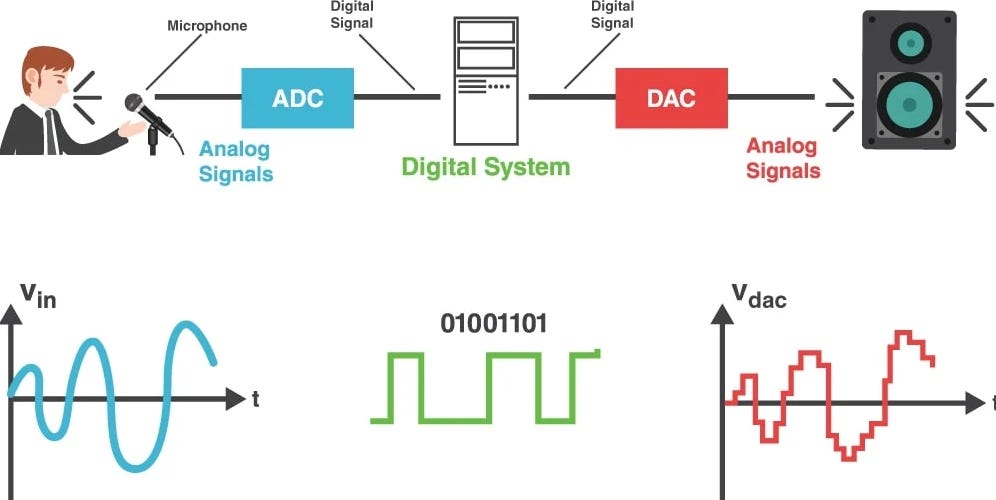

So, there are a few transformations. We take an acoustic signal and turn it into an electrical signal. Then we turn that electrical signal into a digital signal if it’s going into a computer. Then if you are playing that sound out of the computer, it is we’re going back from digital to acoustic. Is that right?

Yeah. It's going from vibrations in the air to positive and negative voltages inside this electrical system to a computer that's turning those voltages into ones and zeros. The original vibration is continuous. Computers can’t represent continuous signals, so it creates a representation of that continuous signal. It’s so close that at sufficient sample rates our brains can’t tell the difference, though.

You work for AEA, which specifies in ribbon microphones. Can you tell me how ribbon mics are different from other mics?

Ribbon mics are a thin strip of aluminum leaf, which at AEA is either 1.8 or 1.2 microns thick. Other companies range from 0.6 to 2.5 microns, though. 1.8 microns thick is about 1/30th of the thickness of an average human hair, so it's very thin and difficult to deal with. After the aluminum leaf is corrugated through two interlocking gears, it becomes springy. That springiness allows it to both move but then stay within the center of the magnetic field created by low carbon steel and neodymium magnets. When you speak into a ribbon mic, that aluminum ribbon vibrates back and forth and creates an AC electrical signal. I think it captures sound so accurately that when you listen back to the recording, it sounds just like it did in real life.

There are always tradeoffs, though. You have dynamic mics like the Shure SM58 that are basically indestructible. While ribbon mics aren’t as fragile as people like to believe, they need to be handled a bit more delicately. At the same time, ribbons get a much better high and low end frequency response than dynamic mics. There are other mics too. Condenser mics work in a completely different way. Those mics use changes in capacitance from the vibration of a diaphragm. I think condensers tend to have a harsh or piercing high frequency response. I know I'm biased since my whole career is in ribbon mics, but I just think they sound more natural than anything else.

The sense that I’m getting is that an AEA ribbon mic is trying to capture sound as accurately as possible. Is that true?

Generally. I won’t bore you with the most technical details, but I think it is important to reiterate that there are always tradeoffs when building a mic. Maybe you want a lower noise floor or higher output, but to do that you need to have a worse high frequency response or a complicated and expensive magnetic structure. It’s up to the designer to make those decisions.

I know that AEA was founded to repair old RCA microphones. Why was there so much demand to repair a vintage mic in the 1980s? Does that demand for repairs still exist?

Repairs are still a big part of our business. I like to compare it to piano tuners. There will always be some demand for piano tuners. You aren’t going to have tons of people doing it in one region, but there’s usually one person or company who does. Vintage mic repairs are similar. The demand is still there. People who use these mics swear by them. Since they can be delicate, people are willing to pay to keep them in tip-top shape.

My assumption would be that microphone technology has improved immensely since the first half of the 20th century. Why do people still want to use these older mics?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Can't Get Much Higher to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.