Making Music Work in Your Town: A Conversation with Shain Shapiro

Shain Shapiro changed my thinking about cities and music. Can he change your thinking too?

If you’re reading this newsletter, you probably love music. Or at least you think you love music. I met Shain Shapiro a few months ago, and he taught me that even though most people claim to love music, our civic actions can sometimes make it harder for music to thrive and musicians to survive.

Shapiro has founded two organizations - Sound Diplomacy and the Center for Music Ecosystems - which conduct evidence-based research to build music ecosystems and demonstrate how music can catalyze larger social change. We spoke last week for an hour about how to grow the global music industry, how local policy can impact working musicians, and his new book, This Must Be the Place: How Music Can Make Your City Better, available now via Penguin Random House.

A Conversation with Shain Shapiro

One of the major through-lines in your book is that we have a paradoxical relationship with music. Nearly everybody agrees that music is important to them and their community but few of those people and places actually have attitudes and policies that reflect that. I want to quote a passage from the book that captures this idea:

Few parents dream of their children becoming musicians … Music is what you do after work. It’s important to learn how to play the piano or the violin … but thinking that it is a path to paying off a mortgage is another thing altogether. This is a deep-seated prejudice that flows through all of us. We all love music, but it is not a serious job, right?

Can you go through some ways that people are actively hostile toward music even though most claim to think it is important?

I wouldn't say that people are actively hostile. I think hostility comes through bad planning and a bad understanding of music's role in the community. You might look at noise complaints as hostile, but that’s really a planning and land-use issue. Nevertheless, I think music has the problem of ubiquity. We take things that are ubiquitous for granted, like clean water. If you’re not familiar with how things that are so ubiquitous get to you - like running water - then you unintentionally take them for granted. You always assume they are going to get to you. Music falls into that bucket.

That’s an interesting point. I think in the last 20 years as we’ve shifted from physical to digital distribution of music the confusion people have about how music gets to them has become even stronger. Is that where you think the disconnect arises?

I think it's even one step beyond that. And before I say what I’m about to say, I want to be clear that it isn’t a criticism. There's no value judgment here. But most people have no understanding of how music is made and how music works at its most basic level. I’m talking about how music is created in a studio. Most people aren’t thinking about how the sausage is made. They’re just happy that they’re getting delicious sausages.

It becomes even more confusing because there often isn’t a physical product with music. You're not a car dealership selling cars. Musicians are selling something that you can't see and often can’t touch. Much industrial trade policy is focused on things that you can see and touch. You can’t touch intellectual property. If there is no foundation for intellectual property to function in a place then music cannot be an economy.

I don’t think many musicians even have a complete view of the intellectual property rights that they have when they release a song.

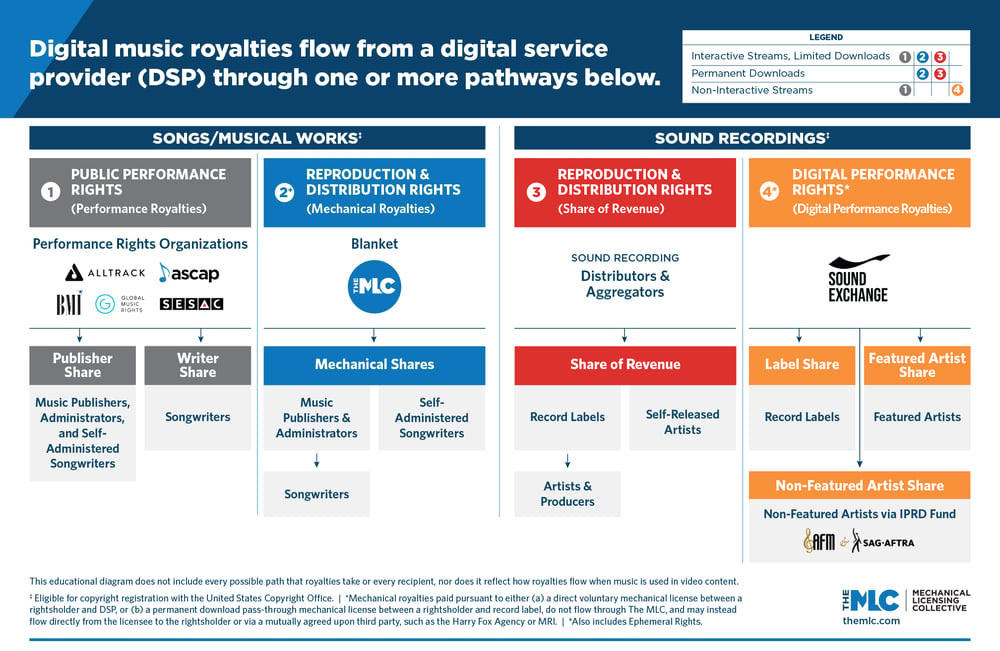

Yeah, I think that's another issue. To me, there's two or three different levels of rights. There are rights in general, like understanding that they are a thing that is worth money. There's also understanding the basics that there are two sides to musical intellectual property, the song itself and the recording.

So, if you don't have a clear understanding of what exists and why it matters, then you’ll never understand how it works at a basic level. Musicians, rightly so, struggle to get their head around that a composition might have 40 or 50 different ways of making money.

But you have to remember that in most places music is not even established as an economic opportunity. There is no music economy in most countries. There is a music ecology. There is a music utility. There is music as a public good. But there really isn't a music economy. For that to exist, you need governments to recognize music as an industry. You need governments to enforce intellectual property rights. You need them to recognize music as a taxable revenue that can be invested into public services.

You started the Center for Music Ecosystems, which is working with the United Nations on establishing global music policies. One of the major initiatives you’ve been working on is expanding intellectual property rights globally. Can you tell me a bit about that?

The technology exists to create music economies. The policy also exists. We all understand what the solution is. It works in many countries around the world, yet there are over 100 countries in the world that lack a functioning copyright management framework.

I set up the Center for Music Ecosystems to try to solve these problems. For the record, these problems usually aren’t specific to music. They're part of bigger problems around poverty, economic growth, climate, and gender equality. I think that if we position music as part of the solution to a bigger problem then we can create more substantive change.

Do you have an example of that?

Imagine you’re in a conflict area and a musician’s house is bombed. Wouldn't it be amazing if they could still get a check the following month because they own the rights to their music and have their compositions represented?

We're working with a few United Nations agencies to incorporate an understanding of music as an economic opportunity into a much wider policy framework. That sounds quite wonky, but it's just a way to explain to global governments and member states how music works and why it matters.

One thing that comes up in your book is that even in places where there are well-established intellectual property rights, music often only interacts with policy indirectly, like via noise violations or public intoxication laws. What do you think the benefits are in addressing music policy directly?

In the first chapter of the book, I write that if there is no policy, it doesn't exist. When a city doesn't have a music policy, then music gets governed by other things like liquor laws, housing laws, and environmental health laws, which is what noise and sound fall under.

For example, when houses are built next to existing music venues, issues can emerge if there is no policy in place. Whose responsibility is it to mitigate the sound? Is it the venue? Is it the housing developer who knew they were building near a venue? I believe that in those situations being proactive is better than being reactive.

You mention in your book that even when places do have public policy related to music it is often discriminatory. For example, there might be spending on some concert hall that has events for opera, jazz, and ballet, but there is rarely funding, say, for DJ booths. Should policy ultimately be agnostic toward musical style?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Can't Get Much Higher to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.