Immortality in 7-Seconds

Almost 40 years later, the Amen Break remains as vital and confusing as ever

Every few days, I scroll through the top music apps on my iPhone. Usually, things are fairly status quo. Spotify. Shazam. YouTube Music. All the stuff you’d expect. But occasionally an app catches my eye that had previously eluded me.

That happened this week with a somewhat peculiar app reaching the upper echelons of Apple’s paid music app chart. It’s called “Amen Break Generator (Revived).” In many ways, it signifies both the past and present of music. As always, this newsletter is also available as a podcast. Listen on Spotify and Apple Podcasts or click play at the top of this page.

Immortality in 7-Seconds

By Chris Dalla Riva

Sometimes an artist knows when they strike gold, when what they’ve recorded is destined to be heard for generations. Usually, that’s not the case, though. Scores of artists tell stories of how they recorded a song as a throwaway, and it unexpectedly helped define their career.

Black Sabbath’s “Paranoid”, for example, was recorded as filler for the group’s sophomore album. It’s currently their most popular song on Spotify and most played in concert. Still, even if it was unexpected, the heavy metal icons at least got to bask in their success. The Winstons didn’t really have that privilege.

Led by Richard Lewis Spencer, a onetime saxophone player for both Otis Redding and The Impressions, The Winstons were an interracial soul group that emerged from Washington, D.C. in the late-1960s. They released one proper album, 1969’s Color Him Father. The title track from the record was a legitimate hit, peaking at number seven on the Billboard Hot 100, and winning Best R&B Song at the 1970 Grammy Awards. But the group wasn’t around much longer.

Spencer soon left the music business to pursue his higher education. According to a Washington Post story from 2006, he “worked for the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority until 2000 and eventually returned to North Carolina to become a high school social studies teacher.” As he made a career in public transit, Spencer probably assumed his music was being forgotten. He was wrong.

When The Winstons were getting ready to release “Color Him Father” as a single, they quickly recorded an instrumental for the B-side. It was based on some gospel music Spencer had played during his days with Curtis Mayfield and The Impressions. Frankly, it was barely a song. It was the same feverish piece played two times separated by a 7-second drum break. “The band didn't really want to rehearse the song,” Spencer told the BBC in 2015, “so I was kind of rushing it.” And when that rush was done, they gave it a name that suggested its gospel origin: “Amen, Brother”.

As I was writing this, I played “Amen, Brother” for my girlfriend. She had never heard it before. Her reaction after hearing it was brief: “There are no words. I liked the trumpets. If I weren’t sitting, I would have danced.” Then she paused. “Oh, yeah, and there was a drum solo in the middle.” It is because of that drum solo — again, which only lasts 7 seconds — that “Amen, Brother” is immortal. Here is how The Economist described it in 2011:

One minute and 26 seconds in, the horns, organ and bass drop out, leaving the drummer, Gregory Coleman, to pound away alone for four bars. For two bars he maintains his previous beat; in the third he delays a snare hit, agitating the groove slightly; and in the fourth he leaves the first beat empty, following up with a brief syncopated pattern that culminates in an unexpectedly early cymbal crash, heralding the band's re-entry.

Upon release as the B-side to “Color Him Father”, “Amen, Brother” made no impact. And it would continue to have no impact for over a decade. Two related developments changed that: the rise of hip-hop and the establishment of Street Beat Records.

To make a very long story short, hip-hop emerged in the Bronx in the 1970s. Progenitors of the genre like DJ Kool Herc realized that when they were spinning records at parties that dancers had the most fervor during the rhythmic breaks of songs. With two turntables and two copies of the same record, these Bronx luminaries could extend those rhythmic breaks as long as they wanted. Emcees soon started shouting over these breaks, often in rhyme, to keep the party going. Thus, hip-hop was born.

Finding exciting rhythmic breaks was no easy task, though. Some artists turned to early drum machines to make their own. Others dug through crates of records to find breaks on older records. In the early 1980s, Lenny Roberts and Lou Flores teamed up to compile, edit, and sell the best older breakbeats on a series of albums put out by Street Beat Records called Ultimate Breaks and Beats. Along with cuts by The Monkees and Rufus Thomas, the first volume contained The Winstons forgotten instrumental. With its release, it was to be forgotten no more.

According to WhoSampled, “the world's most comprehensive, detailed and accurate database of samples, cover songs and remixes,” “Amen, Brother” is the most sampled piece of music of all-time. It’s provided the backbeat to songs by N.W.A, David Bowie, Lady Gaga, Salt-N-Peppa, 100 Gecs, and literally thousands of others.

The Amen Break — what the 7-second snippet in the middle of “Amen, Brother” has become known as — is also the foundation of entire genres. Both jungle and drum and bass, two electronic styles that emerged in the United Kingdom in the 1990s, are arguably built around the sample. To this day, if you search in various electronic music communities on Reddit — like r/DnB, r/breakcore, r/TechnoProduction, and r/Jungle — you will find producers asking about the break and where to download samples of it.

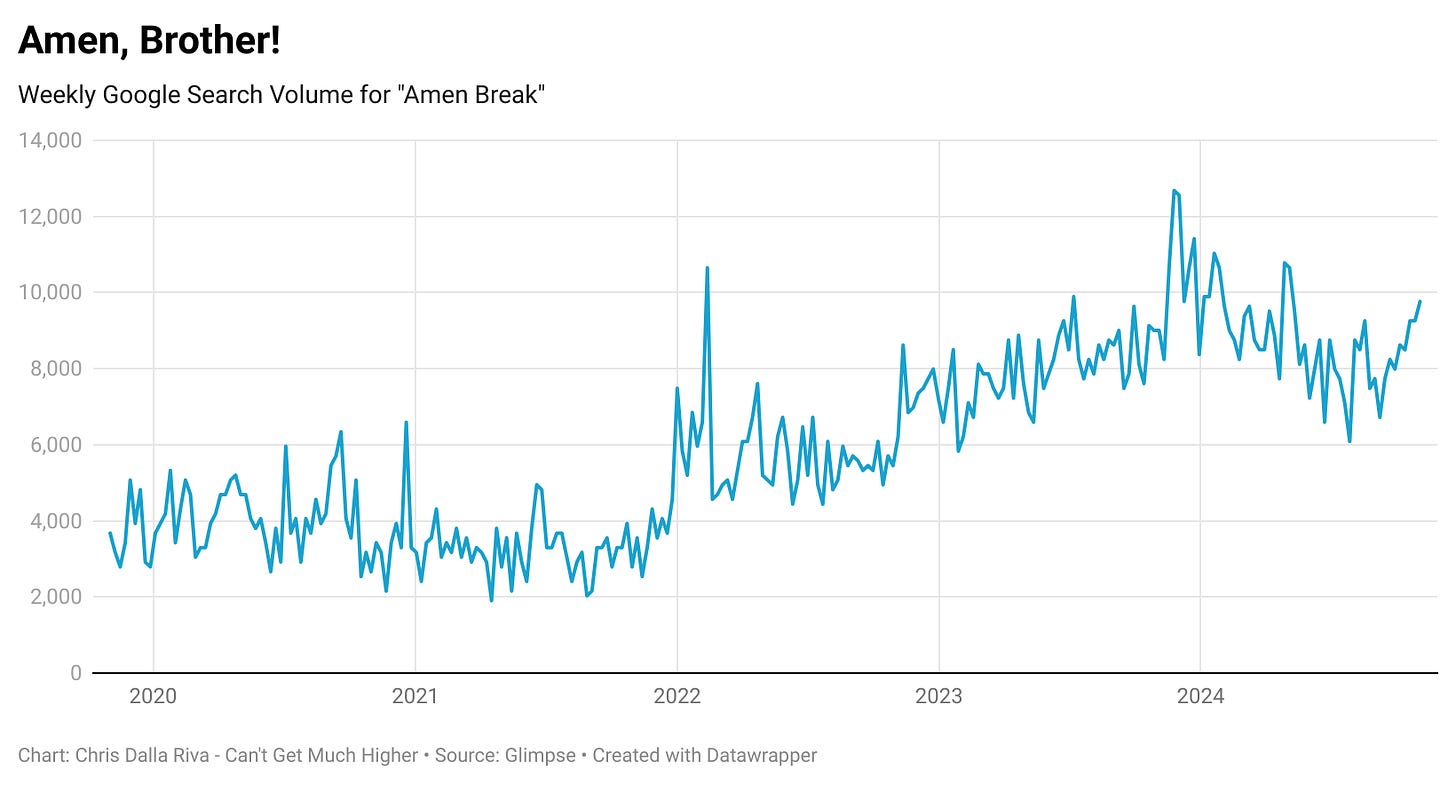

And there’s no signs of its popularity dissipating. The “Amen Break Generator (Revived)” app that I mentioned at the beginning of this piece is a simple tool to create, modify, and download the Amen Break. It’s currently one of the most popular paid apps on the App Store. Furthermore, Google search volume for “Amen Break” is at its highest volume in five years having grown 166% to around 10,000 searches per week.

The continued popularity of the Amen Break forces us to confront deeper questions, though. While Ultimate Breaks and Beats already made the break a staple in hip-hop and electronic music communities by the early 1990s, Richard Lewis Spencer — The Winstons’ frontman — had no idea. According to The Economist, Spencer “only became aware of its rebirth in 1996, when he was phoned by a British music executive seeking the master tape of 'Amen, Brother'.” Needless to say, Spencer never saw any royalties despite his influence.

But was the influence really his? The horn melody bears strong resemblance to “Amen” by The Impressions, the Curtis Mayfield-led group that Spencer had previously played with. Mayfield and his band did not write “Amen”, though. It was composed by Jester Hairston for the 1963 film Lilies of the Field starring Sidney Pointier. Should the song’s success have benefited Hairston? People were sampling a recording that contained a melody he had written.

Then again, artists were not sampling that melody. They were sampling the drum break played by Gregory Coleman. Coleman didn’t own any part of the copyright to “Amen, Brother”. In fact, when he died homeless and addled by drug addiction in 2006, he likely had no idea of his lasting impact.

Each time I hear the Amen Break appear in another popular song, I think of these complexities from both legal and ethical perspectives. Who owns the art that we make? What duty do we have towards those that make it? Does that duty change over time? And does it change if we deem a piece of art to be great? I don’t have any solid answers to these questions. But I do know that no matter how you answer them, the Amen Break will live on. And the reason for that is best summed up by a Redditor in the r/breakcore community:

Something about it just sounds good when sped up, slowed down, chopped, distorted, and still being recognizable after that. A lot of drum breaks just turn to mud instead. Basically a happy accident.

Sometimes accidents are a good thing. Sometimes they aren’t. In the case of the Amen Break, I think it’s both, entire musical traditions birthed from 7-seconds of musical magic by men who never got the credit that they were due.

A New One

"Fueled by Yogurt" by Baauer

2024 - Downtempo House

Best known for the “Harlem Shake”, his 2012 single that spawned a viral internet meme, electronic producer Baauer has released a steady stream of singles since his first success. He’s also taken on a professorial role on TikTok, breaking down famous samples and the inner workings of electronic music. When he opened his recent, heart-pumping single “Fueled by Yogurt” with the Amen Break, the history of the sample was surely not lost on him.

An Old One

"Futurama Main Theme" by Christopher Tyng

1999 - Big Beat

The Amen Break is so ubiquitous that it’s hard to really fathom the full scope of its influence. Of course, you can point to scores of artists across the genre universe to illustrate that point. But I think I might have an even better example.

Christopher Tyng, the composer behind the music in such high profile television shows as The O.C., Suits, and Rescue Me, put the Amen Break to use when working on the theme for Matt Groening’s animated sitcom Futurama. Even if you’ve avoided popular music for the last 40 years, some late-night channel surfing might have brought The Winstons eternal groove to your ears.

Shout out to the paid subscribers who allow this newsletter to exist. Along with getting access to our entire archive, subscribers unlock biweekly interviews with people driving the music industry, monthly round-ups of the most important stories in music, and priority when submitting questions for our mailbag. Consider becoming a paid subscriber today!

Recent Paid Subscriber Interviews: Pitchfork’s Editor-in-Chief • Classical Pianist • Spotify’s Former Data Guru • Music Supervisor • John Legend Collaborator • Wedding DJ • What It’s Like to Go Viral • Adele Collaborator

Recent Newsletters: Personalized Lies • The Lostwave Story • Blockbuster Nostalgia • Weird Band Names • Recorded Music is a Hoax • A Frank Sinatra Mystery • The 40-Year Test

Want to hear the music that I make? Check out my latest single “Overloving” wherever you stream music.

Rhetorical question: is the Amen Break the musical equivalent of the Wilhelm Scream?

That break made me think of every 90's and 00's action movie soundtrack. Great article.