Cultural Mysteries & Nick Cage: A Conversation with Zach Schonfeld

Zach Schonfeld is one of the most exciting cultural journalists around today. He stopped by to talk about his latest book and depressing cultural trends

Usually when I interview someone, we focus exclusively on music. Why wouldn’t we? This is a music newsletter. And Zach Schonfeld and I did talk about music. He writes about it constantly, with dozens of album reviews published on Pitchfork just in the last few years. But Schonfeld’s writing is much more varied than that. He’s written about lost Little Women films, Tom Cruise impersonators, searching for long-dead relatives, and so much more. Over an hour, we touched on everything. If you’re interested in his work, pick up a copy of his most recent book How Coppola Became Cage, which chronicles Nicolas Cage’s early years.

A Conversation with Zach Schonfeld

One thing you capture well in your more recent book is Nicolas Cage’s strange relationship with nepotism. He’s the nephew of Francis Ford Coppola, but chose to use a stage name rather than being associated with the legendary director. At the same time, his uncle helped land him some of his first roles and it was all but an open secret that Cage was Coppola's nephew. First, what do you think drove Cage to live with these contradictions?

I think he had this burning desire to carve out his own identity and his own name and to not be trapped in his uncle's shadow. It was like he needed to prove, either to himself or to the world, that he could make it on his own terms without being dismissed as a “nepo baby.” As you mentioned, at the same time he was in several Coppola films very early in his career. Rumble Fish was one of Cage's very earliest roles. That would have been his breakout role, except he happened to land the lead part in Valley Girl right after that, and Valley Girl was a hit at the box office. Rumble Fish was not. And then he was in The Cotton Club and Peggy Sue Got Married, which were both directed by Coppola.

Interestingly, Cage didn't want to be in Peggy Sue Got Married. He thought the role was kind of boring, and it was Coppola who had to twist his arm and repeatedly asked him to star in that film. Cage made a compromise with his uncle. He said he’d do it if he could bring his own wacky, eccentric energy to that performance. And he did. He modeled the character's entire voice after the claymation horse from the show Gumby, which is why he spends all of Peggy Sue Got Married delivering his lines in this really bizarre, nasally tone of voice. As a result of that performance, Coppola has never worked with him again. That was the end of their collaboration.

That’s sort of funny given how well Peggy Sue Got Married did at the box office.

I think that kind of pissed Coppola off more because it wasn't a movie that he particularly wanted to make. He didn't write the movie. It was a director-for-hire job that he agreed to do because he needed the money after falling deep into debt when he made One From the Heart.

Cage actually wanted to work with his uncle again on Bram Stoker’s Dracula. At one point, Cage said that his entire lifestyle was modeled after Dracula. But his uncle wouldn’t give him the role.

Speaking of the oddness of Cage’s person, in the book you discuss the two origin stories of his stage name. One is that it was based off of the comic book hero Luke Cage. The other is that it came from avant-garde composer John Cage. When you consider the totality of Nicolas Cage’s career both of these influences sort of make sense.

There's a lot of duality to Cage. I want to give credit to the writer Lindsay Gibb who wrote a previous book about Cage in which she makes the case that John Cage and Luke Cage signify the two opposite poles of Cage's career. John Cage signifies the arthouse mode of his work, and Luke Cage signifies the action movie side of his career. Part of what makes Cage such a remarkable and unique actor is the fact that he's always been able to excel in very different styles of performance. You’ve got the big, action movies, like Con Air and The Rock, but, at the same time, you have his subdued, brooding work, like Bringing Out the Dead and Birdy and Leaving Las Vegas, which he won an Academy Award for.

To go back to this nepotism idea for a second, why do you think in certain cases viewers don’t care about nepotism but in other cases they find it a cardinal sin? Like nobody seems to care that Nicolas Cage is Francis Ford Coppola’s nephew.

Nepotism is not a new phenomenon in Hollywood. The Barrymore family goes back over a century. The Fondas are basically Hollywood royalty. I think the thing that has changed is people can go on Wikipedia and see who is related to who. That wasn’t the case when Cage came up in the 1980s. And I think he was lucky for that. It wasn't quite as easy to look up who his family was. He was able to achieve fame on his own terms without the general public knowing he was part of this larger Hollywood clan.

One thing that is clear in How Coppola Became Cage is how much research you did. In fact, you conducted more than 125 interviews. Can you tell me a bit about your research process and how you keep all that information organized?

I read a lot of books about Cage, Coppola, and Hollywood of that era. I also spent a lot of time reading old interviews with Nicolas Cage from the 1980s and 1990s, which is the time period the book focuses on. I also dug through many newspapers. I feel like people don’t realize how much stuff never made it to the internet. I visited the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, and they had so many press clippings about Cage’s early years that aren’t online.

Of course, the most important element of the book was the scores of people that I interviewed. Directors. Actors. Casting directors. Cinematographers. Basically, anybody who would talk to me. Luckily, I started the process at the beginning of COVID, so most people were sitting at home with nothing else to do and were happy to chat. Cage is so eccentric that basically everyone who worked with him had an interesting story to tell.

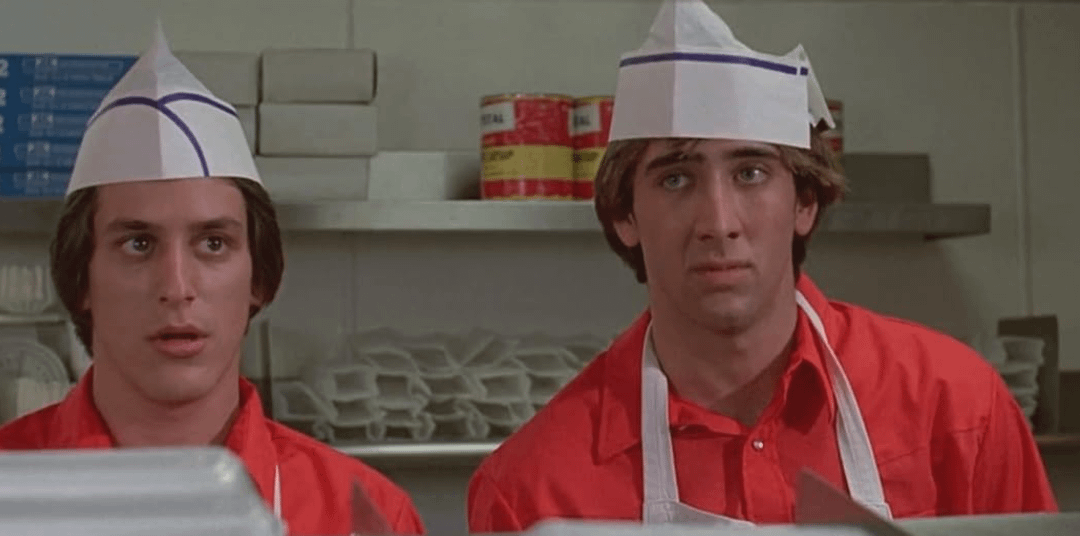

It was nice that I got to talk to some very prominent people in the film industry. David Lynch told me about his work with Cage on Wild at Heart. I spoke with Amy Heckerling, who directed Cage in his first movie, Fast Times at Ridgemont High. I also got to speak with Martha Coolidge, who directed Cage in Valley Girl, his breakout role. I was determined to find stories and insights into Cage's early years that haven't been published before.

It was clear that there were no stones left unturned.

Well, there were one or two. Neither Cage nor Coppola would speak to me for the book.

Regardless, you do paint a very vivid picture of Cage and Hollywood during that era. Were there any particularly memorable anecdotes you heard during the interview process?

Many of his high school classmates had interesting stories. Cage, they related, was in this power struggle with the drama teacher. The teacher was sort of threatened by Cage’s eccentricity. A good example was when they needed to memorize two monologues, one from a classic play and one from something contemporary. Cage just improvised this surreal monologue. When the teacher asked where it was from, he claimed it was some avant-garde French play that he wouldn’t have known. Stories like that are revealing because it shows that he was the way that he was long before he was famous.

One of my other favorite stories was from Mike Figgis, who directed Cage in Leaving Las Vegas. In that movie, Cage plays a suicidal alcoholic. It’s quite bleak. Figgis told me that to embody the character he wanted to be drunk every day of the shoot and have an assistant feed him his lines through an earpiece. Figgis was like, “Absolutely not. That’s not gonna work.” But I think that shows the lengths he wanted to go for that role.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Can't Get Much Higher to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.